An Empire Built With Greed and Sacrifice

Risk and sacrifice are essential if one is going to make great changes within a short period of time. When Japan was forced to thrust open its doors to western powers in the mid-nineteenth century, the Japanese people had a choice: to succumb to foreign influence or to refuse to lose themselves and to push back.

So how do we as teachers tell this important part of history while being sensitive? We don't want to make history class engaging only because they are enthralled by horrifying human stories that remind them of Hollywood movie scripts, but we don't want to be dishonest and sugarcoat the truth. Perhaps an appropriate mix of historical context, primary accounts, and present-day connections, like in this post, is the best approach.

This post is a reflection based on the author's coursework through Primary Source in an online class called Japan and the World.

They pushed back.

But risk and sacrifice had to be a part of the energy behind that push. There are many groups that gave of themselves to make it possible, but the group that stood out to me was women. The victimization of women is an important part of history, but it is incredibly difficult to teach to teenagers in a sensitive but realistic way is a challenge that history teachers must face.

Background Information

For more information on the history behind Japan's journey from a private mysterious samurai culture filled with tradition to a technologically advanced world power that bombed Pearl Harbor, check out these resources:

- Imperial Japan: 1894-1945, Jonathan Lipman

- Japan's New Order and Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: Planning for Empire, Janis Mimura

Unconditional Expansion

Long before Japan chose a side in the World War II conflict, the small island nation had to look for resources abroad in order to keep up with the western imperial powers (Great Britain, United States, France, etc.). They looked nearby to the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, and China. In the Mimura essay, she sums up the Japanese army's strategy to build an empire.The army, on the other hand, found itself bogged down occupying Taiwan, Korea (taken as a colony in 1910), and especially Manchuria, where the army protected Japanese mines, factories, railroads, and large communities of settlers. Eager to demonstrate their power, unwilling to wait for diplomacy, and convinced that their allies in Tokyo would back them, Japanese army officers planned an incident which would force the Japanese government to seize Manchuria. Despite advance warning of the plot, the High command in Tokyo was unwilling to take action against its own men until it was too late. On September 18, 1931, a bomb blast on a Japanese railroad triggered a well-prepared attack in which all of northeast China was seized. By spring, large parts of Mongolia also lay in Japanese hands, and for the next six years, by treaty and by aggressive action on the ground, Japan took over piece after piece of northern China.

Japanese soldiers were hungry for the resources, land, and reputation that they wanted for themselves and for their nation. They were not even willing to wait for word from thier own government when it came to opportunities they saw for growing their nation's global footprint.

Greed

While the soldiers spent months and years away from home fighting for their country, they became greedy. The Nanjing Massacre is the most famous example of mass murder and war rape. In an essay by Mark Seldon:

Major Gen. Sasaki Toichi confided to his diary on December 13:

. . . our detachment alone must have taken care of over 20,000. Later, the enemy surrendered in the thousands. Frenzied troops--rebuffing efforts by superiors to restrain them--finished off these POWs one after another. . . . men would yell, ‘Kill the whole damn lot!” after recalling the past ten days of bloody fighting in which so many buddies had shed so much blood.’”

The killing at Nanjing was not limited to captured Chinese soldiers. Large numbers of civilians were raped and/or killed. Lt. Gen. Okamura Yasuji, who in 1938 became commander of the 10th Army, recalled “that tens of thousands of acts of violence, such as looting and rape, took place against civilians during the assault on Nanjing. Second, front-line troops indulged in the evil practice of executing POWs on the pretext of [lacking] rations.”

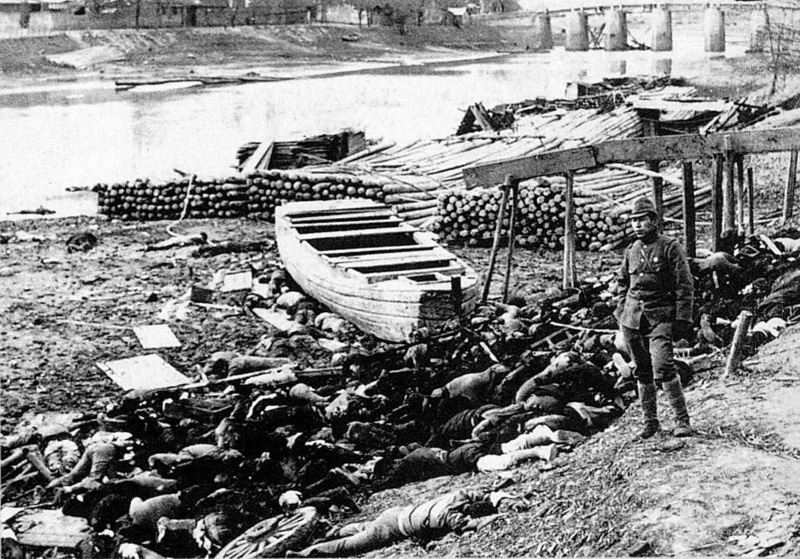

|

| Controversial photo of massacre victims on the shore of the Yangtze River with a Japanese soldier standing nearby. |

Why were Japanese soldiers committing these horrifying war atrocities? Some of the commanding officers thought that separation from home, family, and women could be one of the reasons. They proposed the idea of comfort women.

Comfort Women

Often through trickery, women from Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines and elsewhere were forced to become sexual servants for Japanese soldiers in Asia and the Pacific. Primary sources tell heartbreaking stories of women who were forced into brothels for as many as 8 years.

|

| For more primary accounts see the Digital Museum. |

Many of these women were victimized while their husbands were away at war. When their husbands returned they could not tell them what had happened and lived with the secrets for the rest of their lives. Other young women were kidnapped while their parents were working or were away. These unwilling women made the ultimate sacrifice. Their stories are not told often enough, but they are doing their best to gain recognition and compensation, although neither will make up for what they dealt with.

So how do we as teachers tell this important part of history while being sensitive? We don't want to make history class engaging only because they are enthralled by horrifying human stories that remind them of Hollywood movie scripts, but we don't want to be dishonest and sugarcoat the truth. Perhaps an appropriate mix of historical context, primary accounts, and present-day connections, like in this post, is the best approach.

This post is a reflection based on the author's coursework through Primary Source in an online class called Japan and the World.

19ECE17306

ReplyDeleteGörüntülü Seks

Whatsapp Şov

Telegram Show